Great Asking

In a new series called "The Great Askers" we are exploring what it means to ask better questions and constructing the capacity as a response for the callings of the world we are walking into

We seem to have fallen in love with the form of words that is an answer. Even when we seem to honor those asking questions, notably journalists, they are surreptitiously asking not to be led into the unknown, not to invite out an intelligence, but to appear smart, to 'best' the other.

It is systemic. The forces shaping how we ask, the kind of training we get and what gets rewarded, are precisely toward questions that care more about how the interviewer sounds, and that form of questions is the very same that shut down or embarrass or shame the person being interviewed or is on the other end of the conversation.

Asking great questions, it seems, gets educated out of us. We must do better. This idea is an antidote to that.

In a new series called "The Great Askers" we are exploring what it means to ask better questions and constructing the capacity as a response for the callings and reckonings of the world we are walking into.

A practice of cultivating questions

Behind the scenes of each spoke of the Flourishing Commons, each essay, each Origins Podcast episode, each Flourishing salon, is one of the great struggles and joys of the creation: the search for questions, new and old, insignificant and immense, articulated and ineffable. Indeed, the exhilaration of searching for, crafting, and asking questions (being a student of asking as it were) has been the wellspring of nourishment for making these commons.

Why I listen to, make, and love interviews is because they are a way to listen to another mind, which is to say observe it in action. The best askers understand that and ask such that they inspire the utmost modes of the interviewee's thinking while also becoming invisible when that motion is happening so as not to disrupt it.

For any interview that I do, I spend weeks reading the guest, compiling pages of questions to ask them. The questions that I prepare are rarely the ones that I ask, but they are inextricable in preparing me to create a hospitable space for the conversation that will occur. I write them and revise them for the space they might created, altering them to be not the ones I want to ask but those the interviewee might want to answer (wisdom I received from Krista Tippett). The guiding principle is that questions must be generous, must make an invitation. In this practice of crafting questions as making and holding space, I'm often reminded of French existentialist philosopher and activist Simone de Beauvoir's vision of freedom: a stretching of ourselves into an open future full of possibilities. In this sense, questions help determine our very autonomy and self- and collective-actualization. In Kevin Kelly's words, "A good question creates new territory of thinking. A good question is what humans are for."

The art of asking feels like a literacy we need to cultivate, a prerequisite or core part of the curriculum of the future. I've used this phrase before and it warrants a note of clarification. It is one I've been using to refer to the set of capacities, literacies, skills, and knowledge we need for, as Krista Tippett says, the callings and reckonings of the world we are walking into. The term curriculum is chosen deliberately. Curricula are ideological frameworks. Their purpose is to build a power of recognition and discovery that can then be put into practice. A curriculum is a structure, it is scaffolding, for speaking about something, for transmission. It is a boundary object and thus it is a meeting place of languages and contexts. It is articulation of pathways between. The curriculum of the future is a living attempt to discern a pathway from where we are to where the dynamics of the world around us beckon us to be. So this curriculum I write about is a meaningful structuring of the capacities we need for now. There will be more on this curriculum in a future post.

As a lover and maker of lists, they became a natural receptacle for me to collect ideas and language for new questions. In those lists, which I keep under various headings in my phone and on papers around my desk, I cultivate my sensibility for asking. Now, as we talk about the gravity of becoming better askers as a societal imperative, I'm reminded of the great Italian novelist, philosopher, and cultural critic Umberto Eco's identification of the list as the origin of culture, as cultural achievements in their own right. I think we need to share the lists we keep and our rituals for asking better questions.

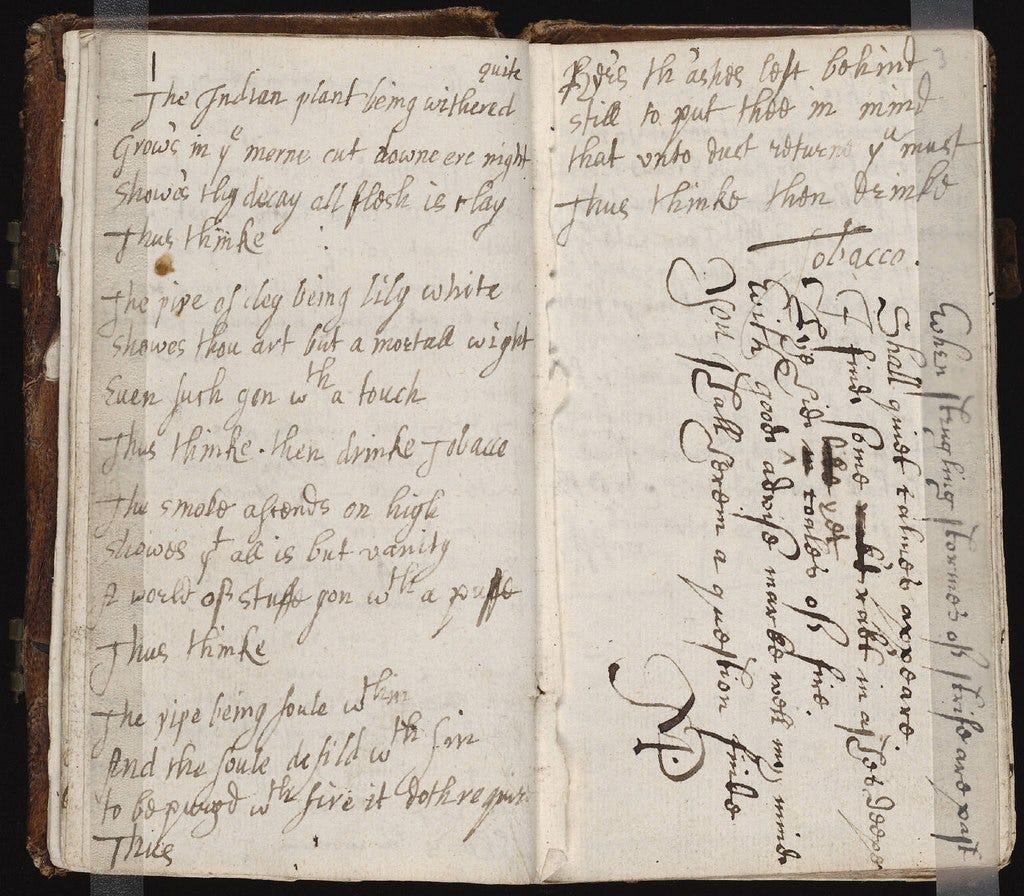

Years ago, in a kind of collision of lists and a commonplace book, I began keeping a note in my phone called "Big Questions to Ask Myself." The idea was simple--as I went about my day (working, researching, reading, exercising, playing with my daughter, daydreaming) I encountered questions that struck me in some way. These might be questions that others posed to me, that I read in books, that I heard in interviews, or that I authored myself, but they all shared the quality that they gave me pause. I needed a place to put these for later reference, in my own writing or work or as material for contemplation or inspiration. And because I have noticed that when I write things by hand, they seem to become a part of my subconscious in a different way than when I type them on a computer or phone, I also began jotting down these significant questions in my pocket commonplace book.

For instance, the very first entry is a question I wrote when encountering a note in Janna Levin's A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines about how we are limited by our experience, "Why do I continue to seek the same experience every day?"

Here is a prompt to invite everyone to join this conversation about Great Asking:

Start a "Big Questions to Ask Myself" note on you phone or in a small notebook you carry around with you and share in the comments to this essay the big questions you discover or yourself author or share lessons you learn about the art of asking.

A living conversation on 'Great Asking'

Words matter. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote, "Words create worlds." Better questions come not only in the intention with which they are conceived, but also the specific way we structure them. The art of great asking is in the subtlest framing of the sentence.

So, we need a conversation about where and how questions are born and how they are articulated and what that articulation means for what follows.

Alongside a number of dear friends, Sara Hendren and Krista Tippett and in the Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences' Wonder Workshops among others, we’ve been cultivating plural conversations about the art of asking.

Now, on the Origins Podcast we are starting a new series called ‘the Great Askers’ — the people changing our society's questions and with them what is possible — to center the philosophy and practice of asking questions. We are talking with the people asking the most meaningful, searching, not necessarily easy questions and on their process for constructing those questions.

In this series we will explore people who have cultivated a singular sensibility of asking and draw out that sensibility — how it developed, how it is developing, what the practice looks like, what are the unseen difficulties and perhaps dark moments. The series will be a collective conversation among the people changing the questions that make so much that is new possible.

Following the Origins style, we will attempt to draw out the why that was inexorable in their lives that they could not go on without asking.

So these will be conversations for anyone engaged with asking better questions: scientists, teachers and parents, interviewers, journalists, podcasters, philosophers, activists and change-makers, those seeking mindfulness. Ultimately, the purpose of this series will be to nourish a sensibility of asking and to cultivate Great Askers in anyone trying to live a life with more purpose.

We've been learning the capacity to ask for five years of Origins, salons, and, more recently, these commons. That learning extends decades back into my own roots as a scientist (the scientist, after all, is not a person who gives the right answers, but the one who asks the right questions French philosopher Claude Lévi-Strauss famously said). This learning puts us in conversation with the earliest roots of science and natural philosophy. The new series will be about rediscovering our capacity for Great Asking and refashioning our great questions anew.

The first episode of the Great Askers will feature Krista Tippett and Sara Hendren, each a kindred spirit in these fascinations.

A clip from the upcoming episode of the Origins Podcast, the inaugural in the “Great Askers” series with Krista Tippett and Sara Hendren

Each episode will be accompanied by a reflection on what we are learning about the art of asking.

A 'Better Questions Guide'

The goal will be to write the 'Better Questions Guide' as a complement to the On Being Foundation's Better Conversations Guide. That guide helps ground and animate a gathering of friends or strangers in a conversation that might take place over weeks or months. In it there is a note on the margins, an invitation to reflection, to ask generous questions. We, each of you reading and those of us in conversation, are taking up that invitation.

Sometimes the questions in my "Big Questions to Ask Myself" lay dormant for years or they never consciously resurface, but I often have glimmers where something that I've written there flashes in exhilarating association with something I'm doing now. These exuberant moments are lifting and nourishing. They create in me an indelible interest in the relationship between questions and generative narratives of our time and taking a long view of time. The Better Questions Guide will adopt these as guiding virtues.

What I'm realizing is that a power of questions is to put us in a receptive state. A great question assumes that your own silence will follow. I will model that here, pausing now for you to join in the conversation. Here again is the calling:

Start a "Big Questions to Ask Myself" note. Carry it around with you and come back here and leave comments on questions that came to you or things you're learning about Great Asking.

I can think of no finer way to leave this than with one of the preeminent invitations to great asking every penned, “Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.” -Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

With great gratitude,

Ryan