The misconception that sunders flourishing (part two)

A two-part essay on the most debilitating mental model of flourishing and how we reclaim a more robust conception.

Part Two: an ecological and anthropological understanding of flourishing

Read Part One here.

There are two points to a more modern conception of flourishing.

First, flourishing is not a conversation among the privileged, nor is it monolithic, simple, or stationary; It is, instead, a muscular and capacious concept—one that resists confinement to narrow definitions.

Flourishing is the actualization of all beings toward their good. It is a continual process—one of negotiation and dialectic—between individual understanding of their own good and collective well-being created through and above our interactions with one another, all in response to the question, 'How do we live well with and for each other?'

Second, flourishing is inherently contextual and multitudinous. Its construction, therefore, must follow a dialectic and pluralistic approach—one that embraces difference and negotiation rather than fixed ideals.

There is no one single doctrine of flourishing waiting to be discovered. Instead, we must grapple with an inevitable reality: what happens when ideas of the good life come into conflict? An understanding of flourishing in a way that furnishes a better society, better lives to and for each other, that can become a generative narrative of our time, requires a philosophy of unsettledness, which in turn requires the philosophy of dialectic.

A more capacious conception of flourishing

Flourishing is mutual, emergent from a realization of interdependence, perhaps best understood within ecological and anthropological sensibilities.

Quietly, ecology has been a crucible for the formation of modern ideas of flourishing. Ernst Haeckel birthed the term ecology, searching for some portmanteau that at once reached back to roots of our western scientific language in ancient Greek and looked forward to a new field emerging, finding the pairing of oikos (house) and logia (the study of): the study of organisms and their home in this life. So ecology unfolded from the very beginning through notions of relationship and belonging. One of the great realizations from 150 years of ecology—reflected in systems and complex adaptive systems science—is that organisms are deeply interconnected, their ecosystems following a fractal structure across scales. Organisms' lives are entangled with one another at every imaginable scale. Interactions are not independent, but rather ripple along these webs of connection. Organisms and ecosystems are mutual. Yet structure emerges. There is structure at the cellular level and at the ecosystem level; and just as a branch on a tree is a micro-scale of the self-same structure of the larger tree, there is a self-similarity among the structures from cells to ecosystems such that a knowledge at one scale reveals truths at others. In ecology, mutuality and cross-scale similarity are organizing principles.

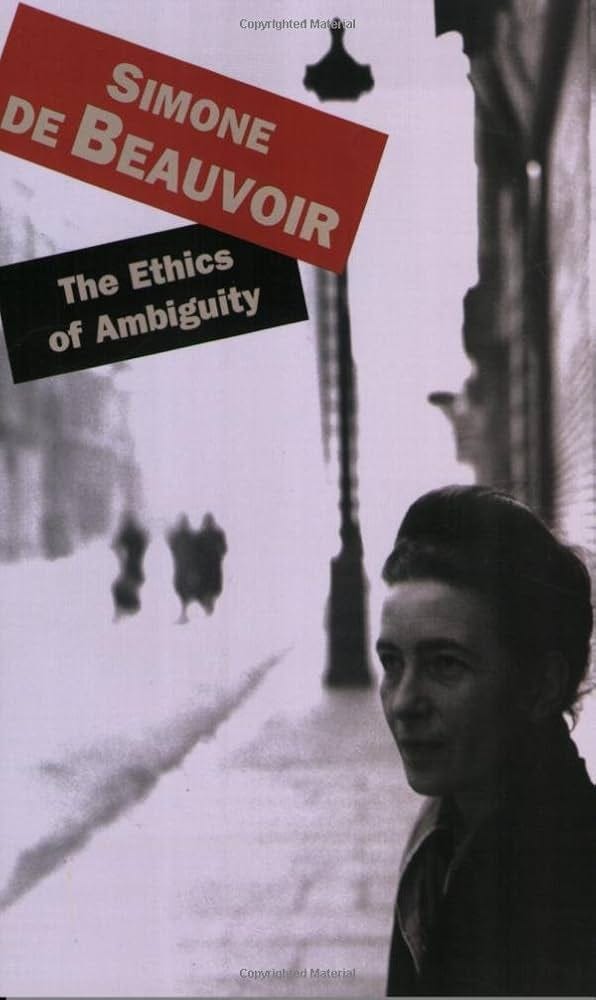

Ethno-botanist and recent MacArthur Fellow Robin Wall Kimmerer finds mutuality to be an ecological lesson for our modern world as well, "In a gift economy, wealth is understood as having enough to share, and the practice for dealing with abundance is to give it away. In fact, status is determined not by how much one accumulates, but by how much one gives away. The currency in a gift economy is relationship, which is expressed as gratitude, as interdependence and the ongoing cycles of reciprocity. A gift economy nurtures the community bonds that enhance mutual well-being; the economic unit is "we" rather than "I," as all flourishing is mutual." She has perhaps inadvertently begun to unify two elements of our understanding of flourishing. The gift economy element gestures toward anthropologist Jame Suzman's definition that flourishing is using our wealth well to enrich ourselves spiritually, enrich ourselves mentally, and do social good. The latter part of interdependence drives us into the articulate words of feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir in describing the genuinely free person: those who seek to extend themselves by means of the freedom of others; those whose ends are the liberation of themselves and others. It is in recognizing interdependence and fractality that ecology teaches us that flourishing for a few or at a single scale is flourishing for none and at no scale.

If ecology gives us the interconnected nature of things, anthropology places those ideas in the realm of human society and culture and thought. Cultural anthropology is the field of understanding cultures and the history of human societies. It reveals a fundamental truth, 'Other peoples of the world are not failed attempts to be you or failed attempts to be modern,' writes Wade Davis. This insight is crucial to understanding flourishing—it must be seen as culturally situated, rather than as a single, universal path. Thus, anthropology furnishes two concepts that identity and relationality depend on: positionality, one's location in relation to their various social identities and how that affects their perception and judgment; and contextuality, the situatedness of a being or a cultural phenomenon within a broader system requiring consideration of social, historical, environmental factors to fully grasp its significance. Both resound for flourishing now. Positionality requires one understand their own perceptions and biases; contextuality calls us to consider the broader system surrounding a thing. Flourishing will be culturally dependent, situated, and entangled; its practices will be self-reflexive and systemic.

An ecological and anthropological understanding of flourishing is emerging. You are not free to be independent in this understanding of flourishing; interdependence reigns, and that feels true to experience. So the 'privileged' or affluent cannot think about flourishing independently. Equally true is flourishing cannot be a thing only possible with economic abundance. Indeed, sages Kimmerer, neither status nor material goods delineate scarcity from abundance in the ecological sense. Flourishing is not class-defined, not a luxury accountable and consumable by the affluent; nor can defining flourishing be merely the idle ruminations of the materially secure. It is mutually experienced and must be mutually defined. And that matters a great deal.

This is hardly the first commentary pointing to these ideas. Yet, it is attempting to bring together and draw upon key bodies of often unassociated work (a reading list follows this essay below). The conversation between them is a rich web of story and implication that this essay will not begin to disentangle, but it is also crucial that we set that process in motion. Four areas of thought stand out:

In 1968, Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Friere proposed a new form of education based on re-imagined relationships between teacher, student, and society. His Pedagogy of the Oppressed emerges from the central tenet that the educated need to co-create the knowledge that is the material of education. He is a dialectical thinker and his philosophy of education reflects the conversational nature of things. He writes that there is no such thing as neutral education. "Education either functions as an instrument to bring about conformity or freedom." We are always positioned somewhere in an ongoing dialectic between oppression and liberation. Finally, his notion of critical consciousness is that to live and to be engaged in your living is a verb, to be in a process. His focus is on the good of all people, for which education is a vital component, and on the local conditions of those people; in short, flourishing as an ongoing endeavor and deeply contextual.

In 1949, French writer, feminist, and existential philosopher Simone de Beauvoir published what is now considered a foundational text in the history of feminism, The Second Sex. A key concept of the work is 'the Other,' the notion that women have historically been defined by their difference from men, effectively becoming "the Other" in a society that centers men as 'agents.' Reading those ideas now, it is difficult to ignore the parallel: just as de Beauvoir critiqued who is granted agency in society, we must ask—who is allowed to be an agent in shaping conversations about flourishing? The Second Sex ignited a tradition in feminist philosophy (and beyond) of fierce challenge to societal norms, to unexamined beliefs--inspiration that looms large in our challenge to accepted notions of flourishing and the good life. She would later relate and generalize those ideas toward a philosophy of freedom, from which we have quoted liberally above, that creates an undeniable bridge toward flourishing.

A contemporary to de Beauvoir, lives lived in parallel itself a source of endless curiosity, Simone Weil was her equal in brilliance if not her counterpoint in how they lived in the world. While de Beauvoir considered herself separate from society, Weil possessed 'a heart that could beat right across the world.' Consumed with an unexampled empathy, Weil wanted to liberate personhood from being defined in terms of commerce and law. She wrote of human needs rather than human rights. Modern philosopher Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen's 'capabilities approach' owes much to Weil's body of work. The capabilities approach is a normative approach to human welfare and a new paradigm for development. It situates the consideration of justice and well-being outside of economic and legal terms, "Justice requires more than giving people an equal amount of goods; it requires giving people equal capabilities to function in certain key human ways and asking what people need to live lives that are 'worthy of the dignity of the human being.' " Dignity, then, is about what people are actually able to do and to be. The idea of capabilities appeals back to Friere's theory of education: Education should be about helping someone build the skills to critically engage with the way the world works, to use their brain to actively engage with the material in a way that produces someone who is capable of understanding their place in a complex world.

In 1990 Elinor Ostrom, in work that would earn her a Nobel Prize, dispelled a decades-long belief that all commonly held resources were doomed to greed and depletion--Garret Hardin's 'tragedy of the commons.' Ethnographic work across flourishing natural resource commons led Ostrom to distill eight design principles for flourishing commons. Those principles are beacons for us as we feel around in the dark for guides about how to live well and for who we are to and for each other. Kimmerer seems to perceive a connection between our understanding of natural resource commons governance and an evolved understanding of societal flourishing, "Anthropologists characterize gift economies as systems of exchange in which goods and services circulate without explicit expectations of direct compensation. Those who have give to those who don't so that everyone in the system has what they need." Ostrom reinforces this ecological understanding of flourishing, emphasizing that sustainability is not imposed from above but emerges from a collective sense of 'enoughness' and accountability in distributing the gifts of the Earth.

Practices of flourishing

These examples disabuse us of our misconceptions that have long plagued and continue to plague the notion of flourishing. Opening the ecological and anthropological perspectives on flourishing suggests that bringing flourishing now requires an embrace of the responses those domains have discovered. Kurt Lewin; systems scientist, MIT professor, and creator the notion of 'action research;' established a principle of change: You cannot understand a system unless you change it. Underneath the pithy language is an anthropological sensibility: you need to participate in the making of change in order to get access to the knowledge that is relevant to that situation. This is the very heart of a democratic system of governance—participation—and a deep truth across societies and ecologies of all kinds. Flourishing is indeed mutual; a commons in which everyone must participate.

We are now called to examine the examples above for the notions and corresponding practices that are clear, consistent, and resolute, a calling that requires radically inclusive civilizational co-creation. Two practices stand out: 1) creating encounters with flourishing and 2) creating new collectives, organized and facilitated in a manner responsive to the hybrid and distributed world we live in that are capable of creating the conception, understanding, and evidence of flourishing drawn from our world's many ways of knowing. Solutions will not be universal. They will be contextual, as varied as our communities. If flourishing is to be a truly civilizational conversation and construction, we need societal structures by which we navigate the ways and places that these contextual solutions intersect, interact, perhaps disagree. Just as a field is a space in which many things meet and coexist and ecological flourishing is negotiated, these intersectional spaces must involve everyone and interactions facilitated (I look toward the domains of peacebuilding and conflict transformation for wisdom). We cannot rely on them arising naturally. We need to actively and steadfastly create them. And we need resources that support all to participate as well as those for the substantial work of peacebuilding. There are examples: participatory democratic structures like citizens assemblies as well as the more mundane yet no less exceptional intersectional spaces like public libraries, public transportation, and sidewalks.

Finally, the work of flourishing is often invisible. Like infrastructure, if a facilitator is doing their work well or a community member contributing to collective well-being, it is seamless; we only seem to notice it when it fails. We don’t bear witness to (let alone write news about) the innumerable small acts that constitute a flourishing community—the influence of these acts is nuanced and unfolds over long time, and nuance and a long view are rare sensibilities in our society. Yet, sustaining such effort toward flourishing is vital. Flourishing occurs at human scale and we need ways to recognize it there. I think the final practice we need is to create nourishing feedback loops. I so seldom tell the people in my life who have had an affect on me about their impact. None of us can know what we mean to other people, and we do each other a disservice by not telling each other what we mean to one another. Finding ways to share these impacts will nourish the acts that create flourishing, becoming feedback loops that change collectives and systems and societies. The acts that create this positive affect, the ordinary and abundant unfolding of dignity and care and generosity, is as much the story of us as any dysfunction or disaster—a generative narrative of our time,1 and one we need to find ways to tell.

Conclusion

The prevailing western, wealthy, industrialized notion of flourishing, colored by a tendency toward dogma and simplification, has been altered altogether by individual and progress (in the industrial sense) orientations to the world. But we cannot escape the fact of ecology, the fact of culture and the anthropology that discovers their co-evolutions and ultimately their connections, the fact indeed of the experience of living. These are our deep shared heritage and it is fitting that their lenses should reveal (read: re-member) an understanding of flourishing more true to our lived experiences, pre-verbal and often even pre-conscious.

Just as democracy is the system to allow more voices to determine what is a good society, we need to radically open the conversation about the good life, what it is to live well together—who defines it, who participates, and what structures enable true inclusivity. Otherwise our conversations about the topic are lip-service, idle ruminations.

There is a core Buddhist comprehension called Pratītyasamutpāda, meaning Dependent Co-Arising or Interdependent Co-Arising. Everything arises in dependence upon multiple causes and conditions; nothing exists as a singular, independent entity, according to the great Zen teacher and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh. He goes on to apprehend the essence of an ecological and anthropological understanding of flourishing:

"the suffering of others is our own suffering, and the happiness of others is our own happiness" -Thich Nhat Hanh

This is an unfinished, always inadequate, beginning of the conversation on a more robust, ecological and anthropological, conception of flourishing, one not constrained to certain subsets of the population but indeed dependent on universal participation and sharing. I'm left with many questions and a great deal of humility, which is, in many respects, the signal of something meaningful. These questions will be showing up in my inquiry--in my conversations, in my science, and in the questions I articulate by how I choose to act now.

Valedictorially, the measure of a thing is the collective it gathers around and beyond it. A collective is nothing if not defined by its questions, so what questions does this leave you with? What uncertainties? Perhaps what discomforts?

Reading list

Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Friere

The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir

The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

Gravity and Grace by Simone Weil

The Serviceberry by Robin Wall Kimmerer

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

Rap on Race by Margaret Mead and James Baldwin

Justice by Means of Democracy by Danielle Allen

Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach by Martha Nussbaum

Governing the Commons by Elinor Ostrom

https://onbeing.org/programs/seeing-the-generative-story-of-our-time/

Amazing post Ryan. There is so much here to contemplate and savor. These are strong foundations to build some of these collectives that you’re referencing. Thank you.